The Hunt

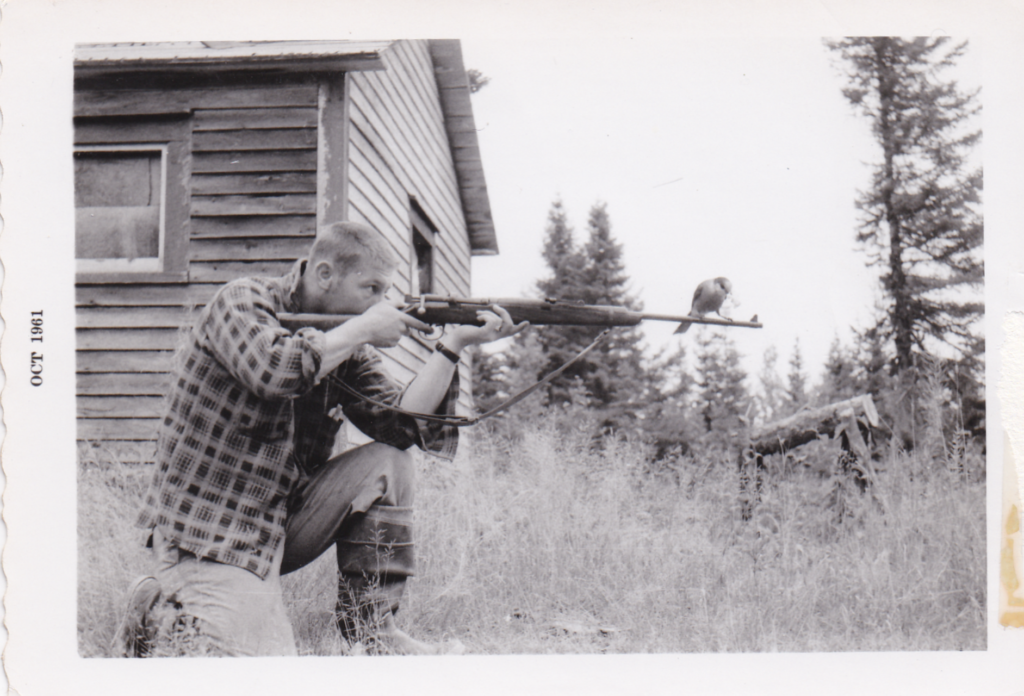

My dad is a hunter and a fisherman, although I can’t personally recall that I’ve actually ever seen him kill anything. I have witnessed him gently escorting quite a few assorted bugs from our home, usually with my mother behind him, shrieking for their death as he apologized for her behaviour and gave them the freedom of the outside. But the evidence of his outdoor pursuits and the death of larger lives were evident throughout my environment.

Tackle boxes and fishing rods periodically lined our hallways, leaning against the walls and cozied into corners. Long and short boots, and caps and coats with vast netting and more pockets than you could shake a stick at lived in the lesser-packed closets of our home. The guns and ammunition were kept locked in the basement, far from the fingers of exploring, stupid children.

There were also buddies who came by and went on the trips, and my brothers, who were sometimes included and sometimes left behind to pine; to watch, to wait, and to wonder. There were many late night and very early morning exoduses from our house, gear in tow, off to the hunt or for the fish. As a girl, I was mostly exempt from the learning of and the longing for the lifestyle of the outdoorsman. But my second X didn’t stop my interest in the whole thing.

I liked the routine and ritual of the preparations and the paraphernalia that came with the pursuit. I liked the strange boots and the secretive hats and jackets. I wasn’t really impressed with the leaving and the disruption to my sleep, although I do remember seeing some nice sunrises because of the commotion. But, as much as I was ambivalent about the departure, I always looked forward to the return.

The homecoming from a trip was filled with excitement, it was a moment anticipated and waited for. For me, my fascination was sometimes baited by my brothers chattering or my mother preparing for any outcome. Other times it was lured by a macabre interest in whatever might be dead on arrival. Either way, the return came with a flurry of activity that was a unique and powerful eddy.

There was seemingly endless unloading. Things moved from one place to another – repeatedly. And in the era before everybody had a phone in hand, there would be only a few exciting snippets of information passed from dad to mom and all of our waiting ears as the gear was unloaded and the hunters finally came in for a rest.

Every hunt, whether triumphant or not, required a recollection; a retelling of what had happened while in the wild. Once the equipment was out of the vehicle, dad and his hunting partners would usually take up a position at the kitchen table, often accompanied by a panting dog with swollen pads sprawled on the floor between them, exhaling hot humid air.

A bottle would appear, glasses would be filled, and the story would begin.

Soon, the room would reek of the deep outside as the earthy and organic odours that had permeated their clothes and skin began to release its perfume in the warmth. It was a smell like no other. It stayed on dad’s gear even after months in the closet. The scent seemed to accumulate like sediment, building up and getting denser with each trip. It was the smell of adventure, the smell of the hunt and the chase, the wind and the weather, the victory of one over the other.

As the account was articulated, I would listen to some of it, catch certain words here and there, but I was much more interested in the results. Anything really big usually arrived already butchered and packaged a day after the hunters came home. When they caught a moose or caribou, they came home empty-handed with only the story and the smell of viscera.

But if the game was small enough, it was in the kitchen while the tale of its last moments was retold. It would be in a basket or bag that would lean against the wall by the door as my dad and his buddies got down to the anecdote of its acquisition and acquiescence.

I came to know that the strange picnic basket that returned filled with fish (or empty) was called a creel. And even though I would never eat them, I would look at them in the basket.

The other bag that sometimes sat in the corner was less structured and softer than the wicker basket the fish arrived in, but much more interesting. It was olive green or some other drab hunting colour and more of a messenger style with a flap over the top and a fastening buckle.

This one always held larger game – birds or rabbits. The very first time I looked in the bag, there was a partridge in it. I was horrified and fascinated as I watched my hand reach out to touch the dead thing while my other one continued to obligingly hold up the flap even though, somewhere deep inside, I wanted to snatch back my hand, drop that flap, and run for cover.

But I didn’t. I touched the bird. It was still pliant – soft and yielding to the touch. And still warm, whether from recently vacated life or the ride back from its former habitat, I couldn’t be sure. It was covered in feathers and certainly didn’t look like anything I could identify or would eat, given my exposure to edible fowl included only chicken and turkey…as far as I knew.

After a while, I began to wonder why my dad would kill moose, rabbits, partridge, turrs, fish, and other things I probably didn’t know about. Yet, time and again, he wouldn’t injure an insect if he could avoid it.

The bags of dead things weighed on my mind when I witnessed his lack of desire to dispatch a buzzing or bothering bug when bidden, preferring to set it free. The paradox was more pronounced in the fall, when the hunting season started. It followed a summer of prime bug invasion due to open doors and windows, and then the in-migration as they tried to find a home inside ours as the weather got colder.

Although it wasn’t a big problem, it was one I wanted to solve. I wanted to know. I began my own investigation into why my dad would kill one but not the other. I had nowhere to look except where I was – so I began my hunt at home.

There was certainly internal evidence of the killing pursuits around our house, but there was probably nothing that would inform the casual observer. There were no antlers exhibited, no animals stuffed, no fish mounted on a plaque – as I had seen in other people’s homes and cabins. If it was killed, it seemed, it was used – dissipated rather than displayed.

I knew the fish were gutted and eaten. I knew that rabbit ended up in a pie or a stew. I knew that partridge was treated like chicken once it was in the house. I knew that the moose was cooked and consumed. (I also realize now that I have eaten more moose in my lifetime than I originally thought, because mom was good at showcasing and selling it as pepper steak). I’m pretty certain the feathers ended up in the garbage, but I know some of the moose fur would be used to tie flies. I don’t know what would happen to the rest of it or the skins of the rabbits – but I assumed they were also used in some way.

I pursued the why and pondered the predicament now and again. Maybe bugs weren’t big enough I thought, maybe they weren’t important enough, or maybe they just didn’t have a fighting chance. I was too young to frame the inconsistency into an inquiry, so I ended up interpreting it myself and coming to a deduction independently.

And the answer I found was as simplistic as I was at the time. Yet it was…elegant. A word I didn’t know then but I feel fits now. It suited my dad very well and I thought it would probably be a good thing for me to remember.

He didn’t kill them because it wasn’t necessary.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m all with mom on the bug thing. I’ve never had the urge, desire, or motivation to kill anything, ever…except for wasps and earwigs. She and I are on the same page when it comes to these critters – destroy or avoid at all cost.

But most other things get a pass from me. I leave any spiders who have taken up residence in my home to their spinning, the ladybugs I find are transplanted to the nearest houseplant, and the carpenters who slowly roam the hallways of my house usually find freedom in the sump pump hole or out the front door with a clumsy pass onto a piece of paper.

I could kill all of them, like a lot of other things I could do.

But I don’t. Because some things – I’ve learned – are just not necessary.

©CRodgers

This was written when my dad was alive. He has since passed.